Most adoptive families invest a significant amount of emotion into their child's Chinese orphanage name. Many use the name as their child's middle name out of a desire to retain a piece of their child's life history. Orphanage names uniquely identify each child, and of interest in this essay are the methods employed by orphanages to create those unique names.

First, a short primer on the names themselves. While many families notice that names often appear the same in the pinyin version, the Chinese characters underlying those names are different. This is due to the fact that many different characters in Chinese can be "translated" into the same pinyin syllable. For example, "Mei" is represented by

forty-one different Chinese characters, six of which (

梅, 美, 妹, 媚, 玫, 媄) are common characters in female names. Thus, an orphanage could adopt many children with the name "Dang Mei", but in Chinese all the names would be different, represented by different Chinese characters.

First Character

The first character of a child's name in Chinese is designated as the surname. Unlike in Western tradition, in Chinese the "last" name of the child is represented by the first character. Thus, my name in China would be written surname, or family name, first: Stuy Brian Harry.

Although most children adopted from a specific orphanage are all given the same "surname", this is not always the case. In Kunming, Yunnan, for example, the surname is a designation of what area of Kunming the child was found in. Thus, children from Kunming may be surnamed "An" (安) if they were found in Anning City, "Cheng" (呈) if they originated in Chenggong, "Guan" (官) if they came from the Guandu district of Kunming, etc. Although surnaming based on finding location is fairly uncommon among orphanages, we will see that it is more commonly used when designating the second character of the name.

While Kunming is pretty straight-forward in its surnaming, other orphanages are less transparent. Desheng orphanage, Guangxi has employed surnaming in an almost "secret-code" method to designate where the children originated from. Desheng is fairly unique among orphanages in that it adopts children transferred from other orphanages in Guangxi Province, including Guiping, Yulin, Pingnan, Cangwu and others, most of whom are also participants in international adoption (Nanning's "Mother's Love" orphanage also adopts largely transferred children from other Guangxi orphanages). The first batch of children submitted by Desheng in April 2001 (when Desheng began international adoptions) was comprised of children mostly from the Cenxi, Pingnan and Guiping orphanages. But in this early group, the surname given to a child is the only clue that they came from another orphanage. In April 2001, for example, seven "Cen" (岑) girls were submitted by Desheng. Although the surname originates in "Cenxi", the assigned finding location was in Desheng. In the same batch were seven children with "Gong" (龚) (indicating an origin in Pingnan) and "Jin" (金) (indicating an origin in Guiping) surnames, all with finding locations inside Yizhou City. In a few cases, finding ads from the originating orphanage lists another finding location, which was of course not conveyed to the adoptive family. For example, an ad for "Jin Xiao Ling" (name altered) was published by the Guiping orphanage on January 13, 2001 listing this child's finding date as December 1, 2000, birth date of November 29, 2000, and the finding location as the Muwa hospital in Guiping. A finding ad for "Jin Xiao

Lin" (name also altered) was published by the Desheng orphanage in April 2001, listing the birth date as December 1, 2000, birthdate as November 29, 2000, and the finding location as "Desheng Northern Temple".

Another girl's finding ad published in the same newspapers give the Guiping information as "Jin Mei Ling, born December 5, 2000, found December 5, 2000 at the Guiping City roundabout" (name altered). The corresponding Desheng ad lists "Jin Mei

Lin, born December 5, 2000, found December 5, 2000 at the Latang Forest Farm in Yizhou City" (name also altered).

A third girl's Guiping finding ad details ""Jin Guo Ling, born November 14, 2000, found December 9, 2000 at the Yu River bridge in Guiping." The corresponding Desheng ad lists "Jin Guo

Lin, born November 14, 2000, found December 9, 2000 at the Desheng main roundabout" (names altered).

After these two groups of children, surnames became uniform for almost all children submitted by Desheng between June 2001 and December 2004, with "Sheng" (胜) being listed as the surname. However, now the finding locations betray the origin of the children, with children found in Qinzhou, Hechi, Xingye, and Cangwu apparently having their finding locations retained, but with a "Sheng" surname given. This would change again in 2005, when both the surnames and the finding locations of the children sent to Desheng were apparently retained. Also of interest is that the children arrived in batches, with each originating orphanage sending 3-6 children at the same time to Desheng. With a few isolated exceptions, this process is still followed in Desheng.

The deceptive "reassigning" of finding locations in 2001 is of course of concern to adoptive parents, who often have no idea that their child did not originate in Desheng, but actually was transferred from Guiping, Pingnan, Cenxi or another orphanage. Another potential problem arises if both the name and finding location were changed, which would then prevent easy detection of a transfer. Thus, in the case of children adopted from Desheng, the surname choice reflected, at least in the early submissions, the area of Guangxi Province where the children originated.

Other common surname methodologies include having the orphanage surname be a part of the town, district or city name -- "Bao" (宝) = Bao'An, Guangdong; "Chen" (郴) = Chenzhou, Hunan; "Ning"(宁) = Changning, Hunan; "Gao" (高) = Gao'An, Jiangxi. This is the most common surnaming method. Also common is the practice of making the orphanage surname the same as the orphanage director's surname --"Lin" (林) = DianBai, Guangdong; "He" (何) = Sanshui, Guangdong; "Qiu" (邱) = Yangxi, Guangdong; "Zhao" (赵) = Yuanling, Hunan.

Surnames can also be based on some characteristic of the area, as in Huazhou's use of the surname "Ji" (吉), which originates from the Cantonese "Jihong", a popular medicinal plant in that area. Other examples are Shangrao City, Jiangxi use of "Ling" (

灵) for its children, originating in the majestic Ling Mountains south of the city, Jianxin, Jiangxi use of "Gan" (淦) after the Gan River in Jiangxi Province, and Xiangtan, Hunan use of "Peng" (彭), the surname of a famous military leader born there.

The two most common orphanage surnames are "Dang" (党) and "Guo" (国), especially early in China's international adoption program. "Guo" (国) is translated as "State" or "Country", and is used to reflect a child's origins in China's State or overall country. Many orphanages have used this surname at some point in their history, including Zhuzhou, Hunan; Beihai, Guangxi; Beiliu, Guangxi, DianBai, Guangdong; Qingcheng, Guangdong; Zhanjiang, Guangdong; and Guixi, Jiangxi.

Another very common surname is "Dang"(党), which represents the political face of China, being interpreted as "Political Party" or "Government". This surname is used most frequently in Henan Province, with more than half of that Province's orphanages using the "Dang" surname at some point in their histories (some examples are Anyang, Hebi, Kaifeng, Luohe, Luoyang, Nanyang, etc.). Other orphanages that use "Dang" include Zhangzhou, Fujian and Ankang and Jiangzhang orphanages in Shaanxi. Other surnames with similar connotations include "Hua" (China), and "Min" (The People, Citizens).

A final example of a common orphanage surname is "Fu" (福), meaning "Good Fortune." It is the root character for "Fuliyuan", the Chinese word for "orphanage", and thus is used to designate a child from an orphanage. This character is used as a surname by the Fuling, Chongqing; Hengdong, Hunan; Sanshui, Guangdong; and Yizhou, Guangxi orphanages among others.

One last use of an orphanage surname is to designate when a child was found. Thus, many orphanages change the orphanage surname periodically (annually, etc.) to reflect the finding time frame of a child. Thus, the Baoji orphanage in Shaanxi used "Sun" (孙) as the orphanage surname in 2002, "Li" (李) in 2003, "Zhou" (周) in 2004, "Wu" (武) in 2005, etc. Other orphanages that have employed similar chronological naming patterns include Zhongshan, Guangdong; Zhuzhou, Hunan; Changsha, Hunan, etc.

Thus, an orphanage surname can be used to designate that a child was an orphan (Dang, Guo, Fu), a city of origin, or a unique aspect of the child's birth city, or when the child was found. In most cases, the surname is chosen to imbue the child's name with some historical or cultural significance.

Middle Characters

The use of middle characters in orphanage names is much more varied, but follows most of the general use patterns found in surnames. Thus, for example, the Shangrao City, Jiangxi orphanage uses the middle character to designate which county a child was found in -- "Cha" (茶) for Chating, "Qian" (铅) for Qianshan, "Wu" (婺) for Wuyuan, etc. Middle names are also commonly indicative of finding time-frames, which can range from just a few weeks to a year or longer. One interesting character that was used by some orphanages in 2008 was the "Ao" (

奥) character (Huazhou, for example, gave this character to every child found in 2008). "Ao" is found in "Ao Yun", the Chinese word for "Olympics" (

奥运), which were held in Beijing in August 2008.

One naming method employed for middle names that I have not yet seen in surnames is the assigning of characters based on the gender of a child. Since 2007, for example, the Qingyang orphanage in Gansu Province has assigned the character "Fu" (福) to boys and "Xiao" (晓) to females. Generally, however, the overall tendency among orphanages is the use of finding location or finding date "codes" when assigning middle characters.

Last Character

The last character (for those children assigned three characters to their orphanage name) is usually the most varied character from any given orphanage. I have not seen any use of the last character to indicate timing, location, or any of the other "informational pieces" that we have seen in the surname and middle characters. But the last character often does follow a pattern, and that pattern is usually the order it appears in a character combination dictionary. Characters in Chinese are not organized by themselves, but rather in groupings based on common usage, or "radicals", with other characters. They are generally listed by complexity of the character, meaning how many strokes it takes to write the character. For our purposes it is only needed to know that characters can be found in "conjugation" groups.

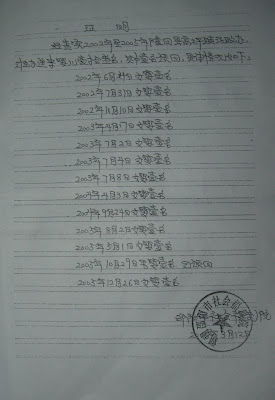

Wuwei orphanage in Gansu gives us a good example of an orphanage almost certainly using a Chinese dictionary in naming children. The image below shows the finding ads for Wuwei orphanage for two consecutive submission batches -- March 9, 2004 (left) and April 15, 2004 (right). The two finding ad scans are four consecutive pages from a typical Chinese dictionary. As one can plainly see, the names for the eight children in the March 9, 2004 and the first child in the April 15, 2004 batch all had the last character of their orphanage name taken from the "Baogaitou" radical section of the Chinese dictionary. The rest of the April 15, 2004 batch all had the last character of their name taken from the "Nvzhipang" radical section, located on the next page of the Chinese dictionary. One child (the fifth ad on the right side) is not listed in our version of the Chinese dictionary, but the last character of her name belongs in this same radical group, and almost certainly appeared in the orphanage's Chinese dictionary. It is extremely unlikely that such naming "clusters" occurred randomly, and they point with certainty that a Chinese dictionary was used.

While most adoptive families imbue their child's Chinese name with emotional meanings, in practice the names chosen are usually (but not always) selected based on a set of bureaucratic and practical reasons. An orphanage may factor in the finding location, the finding date, the child's gender, and lastly a Chinese dictionaries to come up with the name that will be used to identify a child for adoption purposes. While adoptive parents may see the orphanage name as a reflection of a child's history, personality, and character, for most orphanage directors assigning a name to a child is simply a formulaic exercise.