By late June 2006, after numerous suggestions and inputs from "Adoption Today", we discussed how to publish the article. Two alternatives were suggested. First, it was thought to have "Adoption Today" publish the article, with the publication on my blog occurring afterwards. Another alternative was to publish it to my blog first, referring readers to "Adoption Today", which was intending to include several side-bar articles to augment and expand on various aspects of the topic. Richard Fisher and I decided to publish the article first on my blog, and refer readers to "Adoption Today" for further information.

When I published this article on my blog, the response from many in the adoption community was anger and fear. The magazine was flooded with calls and e-mails from concerned families, most of them waiting for referrals. In a deciiosn that I can only assume was made out of fear of losing readers, "Adoption Today" changed its mind and decided not to publish the article. Additionally, Kim Hansel released an e-mail stating:

"Thank you for voicing your concerns. Brian Stuy has inaccurately stated that we will publish his article. As you expressed, there are several inaccuracies in Brian’s piece and as a publication that prides itself on accurate, honest reporting we will not publish what he has to say."

This statement was sent out, apparently without the approval of Richard Fisher, and is completely contrary to the editorial process that had occurred over the past two months.

The evidence presented in this article, obtained from a survey of EVERY orphanage involved in the international adoption process, paints a clear picture of the situation in China. The data presented was obtained from Chinese sources. If there are any "inaccuracies", I wait for someone to bring them to my attention.

The Hague Agreement and China's International Adoption Program

I got the first inkling that things were changing in China’s orphanages when I adopted Meigon in March 2002. As we visited the Guangzhou orphanage and walked the grounds with an officer at the orphanage, I asked her how many domestic adoptions the Guangzhou orphanage does each year. Hedging on the exact number, she replied that there was a three- to four-year waiting list of domestic families seeking to adopt. When I asked her how there could be a waiting list inside China while girls continued to be adopted internationally, she explained that the children adopted internationally had been passed over by domestic families in favor of more “attractive” children.

Experience and research since that time convinces me that the story is a bit more complicated than that. In January 2006, I published the results of my survey of 36 orphanages involved in the international adoption program (See my blog essay, "Domestic Adoption in China"). The results of that survey revealed that most of the orphanages surveyed (85%) claimed to have no healthy baby infants available for domestic adoption, even though adoptions of healthy children were performed for international families.

My conclusions that most of the orphanages involved in the international adoption program had implemented barriers that impeded domestic families from adopting were not universally accepted. Some criticized my sampling methods, feeling that 36 orphanages of nearly 250 total orphanages were not a large enough sample.1 “Your research seems inconclusive,” wrote one anonymous responder. “It is dangerous to make conclusions with incomplete data. I use the word dangerous because you are potentially impacting many lives.”

In order to gain additional insight into this issue, I began in April 2006 to conduct a systematic survey of all the orphanages involved in the international adoption program in China. I employed the same method used for the smaller survey: I had a Chinese national call each orphanage and ask for the director or someone else of position. She represented herself as a married woman, 35 years old, with no children. When asked where she lived, she would indicate that she lived in Guangzhou, but that her husband was local to the city where the orphanage was located. She would ask if there were any babies available for adoption, what the process was, and the fee to adopt. Wherever possible, she engaged the person into a general conversation about infant abandonment, and tried to gain empirical data from each orphanage. I employed this method in order to insure as much as possible that the answers I received were truthful, and intended no disrespect to these directors.

The results solidified the conclusions drawn from my earlier study, that many orphanages have established barriers for domestic families seeking to adopt. However, this complete survey of all the orphanages sheds additional light on the causes of recent trends in the China adoption program.

The first question my prospective adopter asked the orphanage was: “Are there any healthy children under two years of age available for adoption?” Of the 259 orphanages that answered this question(2), 227 answered this question negatively (88%). Of those that replied affirmatively, a few orphanages indicated that a “special relationship” with the director or Civil Affairs Office was required in order to adopt (Chongqing; Gansu), while several others indicated that an adoption could be arranged for a large adoption fee (in excess of 20,000 yuan) (Anhui, Chongqing, Guangxi, Hunan).3 Only 19 (7%) orphanages stated that my friend could adopt a healthy child immediately, with an adoption fee less than 20,000 yuan, although four of those indicated they had only one child available (Guangdong).

When asked why there were no healthy children available for adoption, nearly 36% (86) of the 227 directors that had stated they had no healthy children replied that abandonment of healthy infants has declined over the past several years and that mostly special needs children are now being found. The balance of the directors gave no explanation.

The decline in abandonment rates can be seen graphically by looking at the numbers from the Guangzhou orphanage. Children relinquished to the orphanage can end up in one of four categories: 1) domestically adopted; 2) internationally adopted; 3) remain in the orphanage until they reach 18 years old; or 4) die from illness or neglect. We can determine the first two categories with a high degree of precision by examining the finding ad publications for both groups. “Finding Ads” are legal notices published in various newspapers notifying birth parents that a child will be placed for adoption if unclaimed within 60 days. For domestic adoptions, these legal notices are published upon finalization of the adoption in the Guangzhou Daily, a widely read newspaper.4 For international adoptions, the ads are placed prior to the submission of a child’s paperwork to the China Center of Adoption Affairs (CCAA), the arm of the Chinese government responsible for state-sponsored adoptions.5

It can be clearly seen that the number of domestic adoptions has declined almost 75% over the last six years. The decline is also manifested in the number of international adoptions undertaken by the Guangzhou orphanage.

It seems likely that the declines in domestic and international adoptions are a result of fewer children being available for adoption. Many directors indicated that they felt that economic prosperity had reached their areas to the point that many more families were able to pay the fees assigned to second births,7 and thus no longer felt pressed by financial concerns to abandon their children. Several directors credited local Family Planning strictures with the decline (Hubei, Hunan, Zhejiang). Additionally, the Central Government’s announcement of the “Not One Less” program beginning in 2007 is stated to be having an impact on female abandonment by several directors in Jiangxi Province. This program, announced in March 2006, makes the nine years of compulsory education free for rural families. This saves the average farm-family more than 250 yuan per year (China Embassy, China Today).8 Other factors given by directors for the unavailability of healthy babies for domestic adoptions include fewer babies being found due to selective abortions occurring with the advent of ultrasound (Shaanxi). On the other side of the equation, several directors believed that attitudes in their areas had radically changed over the last few years, and that families were simply keeping their daughters (Jiangsu). Lastly, not a few directors simply replied that their orphanage only adopted children through the CCAA, and not to local families (Chongqing, Guangdong, Hubei, Jiangxi, Liaoning, Shaanxi).

Several orphanages indicated that once a child’s paperwork is forwarded to the CCAA for international adoption, it is almost impossible to retrieve the dossier in order to adopt that child domestically (Anhui; Guangdong). One director indicated that a child is ineligible for adoption until they are one month old, in order that the health and strength of that child can be determined (Guangdong). Many orphanages allow families to take possession of the child earlier, but push the finalization of the adoption (when it is registered) until much later, sometimes up to a year later. When a child reaches three or four months (Guangdong) her paperwork is forwarded to the CCAA for foreign adoption.

My own impressions from my travels and conversations in China is that most of China is seeing a decline in abandonment rates. The main reasons for this decline I believe are two-fold: the increased prosperity of families in China’s countryside, and the decline of “Chinese Traditionalism” which favors boys. Although I see little of China’s traditional bias to males among the young couples having the children in China, many confess to being pressured by grandparents, especially the paternal grandparents, to have boys. I believe that as the older generation dies off in China that abandonment rates will continue to fall (see my blog-essay “The Tale of Two Birthmothers” for more discussion on this point.

But the larger question still remains: Why do the orphanages continue to adopt internationally, while most have a long waiting list of domestic families ready and able to adopt those same children? I believe there are four components to this answer.

There is evidence to suggest that in a few cases children adopted internationally are those that were “passed over” by domestic families seeking to adopt, as the Guangzhou officer suggested. It is a common cultural tendency for Chinese couples to seek out children that will bring honor and respect to their family. Thus, children that display attractive physical features such as large round eyes, double eyelids, and round faces are considered desirable. One orphanage admitted that they had an “ugly” healthy baby girl available for adoption, having been passed over by many prospective families (Guangdong). Another director indicated that he prefers adopting to international families because domestic families pay too much attention to looks, and are thus too picky (Guangdong). Age of the child is also a consideration. Most domestic adoptions involve children less than six months of age. Children found when they are almost a year old or older face fewer prospects of being adopted domestically.

Another barrier to domestic adoption is the health of the child, and the perceived medical expenses that the adoptive family might incur to care for their child. Since most rural (and many urban) families lack health insurance, the potential for expensive medical treatments is a formidable concern for most adopting parents. When given the opportunity to adopt a child with a cleft pallet, for example, most Chinese families would be dissuaded by the expensive medical procedures needed to repair that deformity, and thus pass on adopting that child.

There can be little doubt that financial incentives motivate orphanages to place children for international adoption. I dealt with this particular issue at great length in my blog-article on the finances of baby trafficking. In summary, each internationally adopting family “donates” three thousand U.S. dollars to the orphanage at the time of adoption. In most cases this amount exceeds the donation made by domestic families. I am not asserting that an orphanage director benefits personally from increasing his orphanage’s cash flow by increasing international adoptions. Rather, given the realities of managing an orphanage, any conscientious director would likely do what he or she can to obtain as many financial resources as possible to improve the quality of care in his or her institution. This is especially true over the last few years, which have seen an increase in the percentage of special needs children being found. These children remain longer in the orphanages and require additional resources for medical expenses and care. The international adoption program is thus a price-floor mechanism for the orphanages: Given the demand for healthy infants by foreign families, and the large financial contributions they provide, any remaining children can be adopted to domestic families that also have good financial means. Thus, the revenue to the orphanage is maximized. One director, for example, confessed that although domestic adoption fees had been 6,000 to 8,000 yuan in the past, they had been raised to 15,000 yuan in order to provide additional funding to the special needs children flowing into the orphanage (Liaoning).

Another reason orphanage directors are biased to foreign adoption is the belief that children adopted internationally will have better futures and more opportunities than if they had been adopted domestically. Although it is difficult to say how much this plays into the decision of who is allowed to adopt, it certainly presents an obstacle to domestic adoption.

Lastly, many orphanages have restricted their domestic adoption program to families living in the orphanage’s area. When asked why families from other geographical areas of China are prohibited from adopting from their orphanage, most directors indicate that post-placement reporting is more difficult. Others indicate that given the disparity between supply and demand for healthy baby infants, it is felt that local families should be given first priority.

These factors, taken in aggregate, create significant barriers to families wishing to adopt children inside China. Some of these barriers, such as physical appearance and age of the child, are self-imposed obstacles, and could be overcome if the family would choose to do so. Others, such as the high financial requirements to adopt from most orphanages (ranging anywhere from 10,000 to 30,000 yuan) and future medical expenses lie largely outside the prospective adoptive family’s control. Altogether they combine to make it difficult, if not impossible, for most domestic families to find adoptable children. As one director put it, “many families call, but give up when they are told there are no healthy babies” (Henan).

The Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption

In September 2005, China ratified the Hague Agreement on the Protection and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. One of the primary provisions of this agreement is the recognition “that intercountry adoption may offer the advantage of a permanent family to a child for whom a suitable family cannot be found in his or her State of origin.” Many of us adoptive parents question whether it would be better for China’s children to remain in their birth culture and country rather than being adopted into other lands, often becoming members of multi-racial families. Like many orphanage directors, we wonder which option presents the best opportunities for a child’s life and happiness – domestic or international adoption. But the world community as a body has determined that if possible, a child should remain in their country of origin before being adopted internationally. This understanding was codified in the Hague Agreement, and ratified by China. It appears from all the evidence presented above that China is in violation of that agreement by continuing to place healthy infant children with foreign families when many domestic families are desirous to adopt those same children.

As stated above, my survey of all the orphanages that participate in the international adoption program shows that 88% state that they have no healthy children available for domestic adoption. Below are the survey results for Guangxi Province. This province was chosen because every orphanage indicated to my interviewer that no healthy children were available. Next to each orphanage name is the number of dossiers that were submitted for international adoption in 2005:

Beihai -- 142

Cangwu -- 24

Cenxi -- 28

Desheng -- 70

Guigang -- 67

Guilin -- 113

Guiping -- 109

Hepu -- 64

Jingxi -- 13

Laibin -- 32

Liuzhou -- 55

Nanning -- 118

Pingnan -- 51

Qinzhou -- 39

Rongxian -- 8

Wuzhou -- 50

Yongning -- 18

Yulin -- 125

It is theoretically possible that all of these children were “passed over” by domestic families, or had medical issues which made them difficult to adopt to a Chinese family. However, a survey of 72 families that adopted children from these orphanages in 2005 and early 2006 revealed that only 17% of the children had special needs, with the balance (83%) being classified as “healthy”.9 The directors of the Cenxi, Guigang, Jingxi, Pingnan, and Yulin orphanages expressly stated that there were large numbers of domestic families waiting to adopt (30 to 40 in the case of Yulin), even as they continue to submit healthy children for international adoption.

Clearly, healthy children have and continue to be adopted internationally at the expense of families inside China that desire to build a family. It is possible that the difficulties experienced by domestic families seeking to adopt outlined above are found only in those orphanages that participate in the international adoption program. Thus, perhaps the rest of China’s orphanages that do not take part in international adoptions have abundant healthy children waiting for adoptive families in their facilities. One solution would be to increase participation in the international adoption program to all orphanages in China. This would spread the demand more evenly, and free up healthy children in the current internationally adopting orphanages to be adopted domestically. Given the number of children reportedly housed in these facilities, however, it seems likely that even this would not solve the demand imbalance.10

Another solution, and one which benefits all parties involved, would be to limit China’s international adoption program to those children who are, for one reason or another, “unadoptable” inside China. These would include children over 2 years or those with special needs, which are a growing and pressing problem in China’s orphanages.11 This would allow domestic families to adopt the healthy infants for which there is strong demand. Foreign families, most of whom have access to health care and other corrective medical technologies, would be able to adopt and give a home to a child who would otherwise most likely remain in an institution in China.12

In 2001 the Romanian and Cambodian international adoption programs were closed after it was shown that both countries had significant problems with their international adoption programs.13 In those cases, significant evidence of baby trafficking forced the closure of their programs until adequate safeguards could be implemented. These countries were violating basic human rights, and they deserved to be closed.

China is different. With the exception of the Hunan trafficking scandal reported in late 2005, its program has been the model of legitimacy.14 The issue is therefore much more complex, and focuses almost exclusively on the question of where the adopted child will have the best life and greatest opportunities. Setting aside the Hague agreement, as adoptive parents of Chinese children we must decide who should take priority in adopting these children. I frame the question thusly: I am the director of a Chinese orphanage and have a single healthy infant available for adoption. Two families apply to adopt the child, a middle-class Chinese family and a middle class American family. With whom would I place the child?

Personally, my instinctive reaction would be to place the child with a domestic family. As I wrote following the adoption of my oldest daughter Meikina, I have always felt that the loss of culture, language, country and religion to be important and significant in foreign adoption.15 I mourn the loss of these attributes of China in the lives of all three of my daughters. Tobias Hubinette, himself a Korean adoptee in Sweden, writes a biting criticism of the global international adoption program. “It is assumed that there are no special problems, emotional or psychological costs being a non-white adoptee in a white adoptive family and living in a predominantly white surrounding. Consequently, assimilation becomes the ideal as the adoptee is stripped of name, language, religion and culture, while the bonds to the biological family and the country of origin are cut off. Adoptees who are consciously dissociating themselves from their country of origin and see themselves as whites are interpreted as examples of successful adjustments, while interest in cultural heritage and biological roots is seen as an indication of poor mental health or condemned as expressions of biologism and Nationalism.” Hubinette goes on to quantify the problems of adjustment experienced by international adoptees, and the additional risk these individuals have in areas such as mental health, crime and suicide. He concludes, that given all of these problems, that “in this perspective, it becomes more evident than ever that intercountry adoption is nothing else but an irresponsible social experiment of gigantic measures, from the beginning to the end.”

Many adoptive families would disagree with some of Hubinette’s conclusions. Although Hubinette’s criticisms are directed largely at the Korean adoption program, parallels to the Chinese program are evident. The loss of culture and heritage has compelled many minority groups to come out in opposition to trans-racial adoption, including many Native American tribes. As adoptive parents of Chinese children, we often resist or ignore this problem by attending our FCC parties, teaching our children Mandarin, and participating in other activities designed to instill in our children a sense of “culture.” We must recognize that these are poor substitutes for authentic culture.

This loss, however, is simply the first layer of the onion. Comparing the positive attributes of Western culture to Eastern makes the judgment of what is in the best interest of the child more difficult. China’s perceptions of women, and its bias against women, offer a substantial counter-argument in favor of international adoption.16 Additionally, as many directors in my survey revealed, it is felt that educational opportunities are substantially better in the West. My children will be free to choose how long they will work, where they can live, which countries they visit, how many children they wish to raise, and a myriad other opportunities afforded citizens of the West that are absent from the lives of most women in China. How much these benefits offset the negatives of heritage loss is difficult to quantify and is a topic with which I constantly struggle.

With so many of the orphanages involved in China’s international adoption program reporting significant wait times for domestic families to adopt, it is clear that the number of healthy children available for adoption has fallen below the demand from both inside and outside China. International agreements state that given that circumstance, priority must be given to domestic families. Americans and families in other Western countries should consider this reality when making their decisions on where to adopt, and China must consider changing their program to address these realities. Together, solutions can be forged that benefit all of the children in China’s orphanages, especially those left behind.

_______________________________________

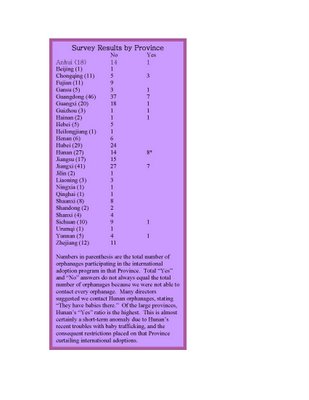

The following table shows the survey results by Province (click on image to make it more readable).

________________________________________

A word on how the orphanages were surveyed: Contact was made by phone, and my surveyor started by simply stating she was a married woman seeking to adopt a healthy child under 2 years of age. No mention was made as to where she lived, her age, income, etc. unless the director asked specifically for it. In over 90% of the calls, the director never asked. A small percentage simply hung up, which we quantified as a no-contact, although it seems likely they hung up because they were uninterested in adopting a child from their orphanage. In other words, I feel we would have received a "No" to our inquiry.

Most directors simply stated early in the conversation that there were no children available. Those that did inquire as to where my surveyor was from almost always indicated that there were children available. In other words, having my surveyor telling a small number of directors that she was from Guangzhou but that her husband was from the orphanage city had no detrimental impact on the results. I composed the script after considering all possible variables, and believe that this method insured the most "honest" answers.

An additional word to accusations about my "agenda": My agenda is simple -- the overall well-being of China's orphans. I certainly understand a difference of opinion as to what is better for a child -- adoption in-country or adoption to an international family. But minds vastly superior to mine have studied and concluded that it is in the best interest of the child to remain in-country whenever possible. We can debate that issue, but it forms the foundation of the Hague Agreement. Although I obviously am ambivalent about this difficult issue, in the international arena it has been decided, and by ratifying the Hague Agreement China has indicated agreement also.

Post Script: On August 12, Researcher/Author Kay Johnson posted the following comment to the blog. Due to problems with Blogger, I am including it here:

Brian, I just found this article on your blog (from a yahoo list) and find the information you provide very valuable. I agree that China adoption practices are not in accord with the principles formulated at the Hague and think your new evidence to this effect adds significant weight to this view. I made a similar argument in a 2002 article I published in Law and Society Review, on "The Politics of Domestic and International Adoption in China." My argument then rested heavily on the way adoption policy restricted domestic adoption at the same time the government opened up to international adoption. I argued that the restrictive adoption policy was a product of population control priorities, not child welfare needs. The policies themselves discriminate against foundlings (in contrast to orphans) and make it difficult for them to find new homes in China by drastically reducing the number of legal adopters in-country.

I also presented evidence from my research that some domestic adopters (those who already had a birth child) faced significant legal obstacles and harassment from birth planning authorities. At that time I had only anecdotal evidence that orphanage directors favored international adoption at the expense of domestic adoption due to the financial benefits (as opposed to merely guarding against the use of domestic adoption to hide overquota children). After the law was revised in 1999 to increase the legally approved pool of adopters, orphanages could have done much more to promote domestic adoption from the orphanage system. But many continued to apply the restrictive childless rule to Chinese adopters who came to the orphanage, while others imposed impossibly high fees on domestic adopters in an effort to discourage them.

Few directors I talked to were interested in seeking out domestic adopters let alone publicizing (though a few did); even people who lived in cities with large orphanages were often unaware of the availability of children for adoption or that the law had been revised to allow people with one child to adopt a second child from an orphanage. Meanwhile even the revised law continued to specify that those who adopted foundlings outside of orphanages (the vast majority of Chinese adopters) still had to be childless and over 30. This was, as before, to prevent people from using adoption to hide overquota children, even though this caused great hardship for many children and the adoptive parents who wanted to raise them. Your research has added a great deal to this picture. Although, as some of the blog comments indicate, it does not "prove" every orphanage prefers international over domestic adoption, it strongly suggests that many of those orphanages that participate in international adoptions do indeed discourage domestic adoption. The way orphanages are financed has weighted the system in this direction.

Your evidence is more than enough to illustrate this point and support your argument persuasively in my view. I believe, as you do, that there are more and more orphanages with a preponderance of disabled children today. These children need homes and cannot find them readily inside China due to the limited resources of most prospective adopters and the widespread lack of decent medical insurance in the countryside today. Increasingly, the children who truly cannot find homes in China need to be the ones served through international adoption. But this will require more changes in the system and the policies that govern it. I appreciate your efforts to promote those changes.

Kay Johnson

__________________________________________

Footnotes:

1. There is some disagreement as to how many orphanages exist in China. China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs reported in 2001 that there were 1,550 state-run orphanages, 160 of which specialized in the care of orphans. These facilities were said to have cared for approximately 41,000 children (Kay Johnson, “Wanting a Daughter, Needing a Son – Abandonment, Adoption and Orphanage Care in China”, Yeong & Yeong Book Company, p. 204). Jane Liedtke of “Our Chinese Daughters Foundation” (OCDF) puts the number of orphanages at over 750, with between 42,500 and 85,000 children institutionalized in those facilities. The number of orphanages continues to rise as China implements their redistricting program. This is resulting in more “district “ orphanages being created in the larger cities. Maoming City in Guangdong Province, for example, has, in addition to the city orphanage, two district orphanages – Maonan and Maogang. The Jiangcheng district orphanage in Yangjiang (Guangdong Province) is located 200 feet west of the Yangjiang City orphanage. A 2004 pronouncement states that “Today, China has 192 special welfare institutions for children and 600 comprehensive welfare institutions with a children's department, accommodating a total of 54,000 orphans and disabled children. My listing of the orphanages that participate in the international adoption program is drawn from the “Raising China Children” Yahoo Newsgroup. This site lists the orphanages for which individual newsgroups exist. These groups are formed by parents whose children were adopted from common cities as a way of gaining information about their child’s beginnings, and to remain in contact with their child’s “orphanage sisters” and "brothers." As of this writing (June 2006) there are 274 of these individual newsgroups, encompassing almost all of the internationally adopting orphanages in China. Additionally, I have added orphanages that publish finding ads for international adoption, even though no Yahoogroup exists. Thus, the total number of orphanages I attempted to survey was 292.

2. We were unable to interview 34 of the orphanages due to an inability to locate working phone numbers, or because the orphanage director simply “hung up” when we called.

3. In order to protect the identity of the orphanage directors, who were unaware that their conversations were to be used for publication, I am not able to identify how specific orphanages responded to individual questions, other than to refer to their province.

4. The term “Finding Ad” is a technical misnomer. The ads are not published to locate birth parents, but rather are legal notices transferring legal custody of the child from her birth family to the state, allowing for her adoption. In contrast to the finding ads placed for internationally adopted children, the finding ads published for domestically adopted children do not describe which orphanage the child was adopted from. In the case of the finding ads placed in the Guangzhou Daily, I relied on my wife’s knowledge of Guangzhou (she is native to Guangzhou) to determine which children most likely ended up in the Guangzhou orphanage. Since the finding ad describes what geographical area a child was found in, we were able to assign with high probability which orphanage they were taken to. Although I have taken great care to discern accurate numbers for Guangzhou’s domestically adopted finding ads, small mistakes were possibly made.

5. Category 3 consists mostly of unadoptable children, those possessing extreme mental and physical disabilities. Since there is little reason for an orphanage not to submit the paperwork for adoptable children, most unadopted children will fall into category 2, since their paperwork has been forwarded to the CCAA, but they have not been referred to a family for adoption. Both category 3 & 4 are difficult to determine, but is seems likely that over the past five years a small and declining number of children would fall into these categories.

6. It is possible that this number is inflated. Since the finding ads started in July 1999, it seems possible that 2000 ads might have been partially comprised of “catch-up” ads from the previous year. However, there was no “catching-up” with the international finding ads – if a child’s paperwork was already in process at the CCAA in July 1999, no finding ad was required to be published.

7. It is widely recognized that the problem of infant abandonment in China is primarily a result of the implementation of China’s “One Child Policy” in 1979. This policy, simply stated, allows urban families one child and rural families one child if that child is male. Rural families are allowed a second child if the first child is female. This policy recognizes a cultural bias to male children. Families that violate the policy by having additional children are subject to fines, job loss, and in some rare cases, forced sterilization procedures (http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/a/onechild.htm). Many scholars have written about China's rising wages, and it is these rising incomes that allow more parents to pay the fines associated with violating the Family Planning strictures against multiple children (http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/display.article?id=2242; http://www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu10we/uu10we0l.htm).

8. Tuition has been free for Primary and Secondary students since 1986, but many rural families have been forced to pay “education expenses” for such things as text books, school heating, etc. The “Not One Less” program addresses these add-on expenses.

9. Families were located through the Guangxi Province newsgroups, as well as previous contact made to me for finding ads. We received health status from 72 of the roughly 1,288 children placed for adopt in 2005 from Guangxi. Sixty were classified as “Healthy”, while twelve had minor special needs.

10. In addition to contacting the orphanages that participate in the international adoption program, we also surveyed two orphanages that only adopt domestically. Both orphanages adopted only to local residents, and both had significant waiting lists of anxious families seeking to adopt.

11. Joshua Zhong, chairman of Chinese Children Adoption International (CCAI), believes that over 50% of the children in China’s orphanages are special needs. I view this estimate as very conservative, and believe it is much higher in actuality.

12. In many ways, this idea would reverse the adoption process that existed until 1999. Prior to that time international families were required to adopt a special needs child if they had other children at home or were younger than 35 years old (Karin Evans, “The Lost Daughters of China,” Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 2000, p. 175). Currently, a special needs child will only be referred to a family that specifically requests one.

13. Monica Youngs, “Overview of Country Shutdowns,” Adoption Today, February/March 2005, pp. 14-17. Romania closed due to pressure from the European Union, while Cambodia voluntarily closed their program rather than face censure from the international community.

14. The Hunan story was disturbing because it is the first known example of children being trafficked to orphanages in order to satisfy unfulfilled domestic and international demand for healthy children. The high adoption fee reported by a majority of orphanages contributes to China’s baby trafficking, I believe. A recent study by Chongqing University’s Zhang Weiguo in the March 2006 issue of Journal of Family Issues reveals that of the 425 domestic families surveyed that had adopted children “50 percent obtained their children through intermediaries (including so-called traffickers), 26 percent from family members, and 23 percent obtained children who were abandoned directly or found by friends, family, or neighbors. Less than one percent of the children covered in the study were adopted from state controlled orphanages.” Given the financial incentives to adopt internationally, most orphanages continue to charge high adoption fees to domestic families seeking to adopt children.

15. Brian H. Stuy, “A Train Ride to Maoming,” Adoption Today, July 2002, p. 46.

16. Evidence of China’s treatment of women, especially in the countryside, is the suicide rate among women -- the highest in the world. China is the only country where more women commit suicide than men (Karin Evans, p. 73).