I remember feeling that my job was getting just a tad routine. Not to the point of boredom, but after visiting more than 50 orphanages, photographing hundreds (if not thousands) of finding locations, and talking with scores of finders, it was all becoming a bit predictable. At least I thought so as I climbed out of the taxi in front of the home of "Hua Mei Xiao" (not her real name). "OK," I said to my wife, "Let's hurry and get this done." I was anxious to wrap up our last finding location -- this little farm house in a village in eastern Jiangxi Province.

We introduced ourselves to the finder, a grand-motherly woman who greeted us in the courtyard of her one-room house. We explained that we were there to find out more about the child she had found 2 years earlier. We had learned that she had also fostered the child after she was found, and wondered how that had come to be.

She explained that when she had found the child, she had contacted the orphanage and reported her. She had been fostering children for many years, so Mei Xiao speculated that the birth parents had probably known that, and that is why they had abandoned the child in her courtyard. It all seemed very logical.

I asked her to point out exactly where the child had been found, and she responded with a sweep of her hand. "Over there" she stated matter-of-factly. Thinking I had missed something, I asked her to show me again. Again she proffered only a wide sweep of her hand. A bell went off in my head.

I don't understand much Chinese, something my wife finds useful when she occasionally lets loose on me in her native tongue. Instead, my wife does the talking, and I do the watching, and as I watched Hua Mei Xiao, I knew that she was hiding something from us.

"Lan," I whispered, "ask her if she knows the birth mother." "Are you nuts?" was her response, but I told her to ask the question. I had a gut feeling.

As my wife posed the question to Mei Xiao she grew instantly quiet and reflective. Finally, after a few moments, she acknowledged that she did.

I grew excited, and machine-gunned questions at Lan to ask. I couldn't believe it! After all these years, I was finally going to be able to find the Holy Grail -- a birth mother of one of my girls.

Mei Xiao led us into her home, and sat us down at her table. I asked her to tell us about the birth mother. She replied that she was about 28, lived on a farm, was married, and had a older girl and a young boy in her family.

As we sat and talked, we discovered that not only did she know the birth mother of the girl we were researching, but also of another unknown child found 9 years ago. After I returned home, I aggressively worked to locate this child, and in September 2005, after watching my project DVD, an adoptive mother contacted me. Her daughter had also been found by Mei Xiao. She was the other girl.

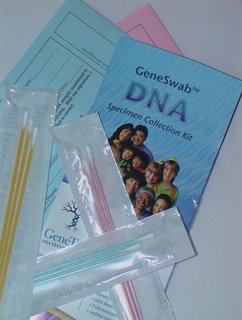

So on this visit we returned to this small village and once again entered the courtyard of Mei Xiao. In my camera bag I carried DNA kits from Genetree in Salt Lake City. Mei Xiao was happy to see us again, and as we reintroduced ourselves, we explained why we had returned. She told us that the birth parents lived a distance away, but that she would arrange a meeting the next morning.

As I sat across from the two women, my heart raced. I wanted to know each of their stories, not just for the families I represented, but for myself. Perhaps the stories they would tell me would parallel those of three other birth mothers, living far away in an unknown place, who in the darkness of a solitary night had also decided to give up their daughters. So, as I addressed these two women, I was asking them questions not just for their daughters, but for my own.

“Li Feng”

Li Feng (not her real name) sat nervously in her brown corduroy jacket and white turtle neck. I assured her that it was safe to talk freely with us, and that no one would ever be able to locate her. I explained why it was important for adoptive families to understand their daughters’ histories, and that what she explained today would be valuable to many families in understanding how their daughters came to be in their lives.

She began by telling me that she was 35 years old, and that she had been married for 15 years. Her oldest child, a girl, was born shortly after she was married and was now 15 years old. A year after the birth of her first child, she became pregnant with her second child. She gave birth to another girl, and so she and her husband placed this child with a family member. Her third daughter was born four years later, and it was this girl who was brought to the orphanage. Soon after giving birth, she contacted a family member that fostered for the orphanage and asked her to see that the child was put in the care of the local orphanage. This foster mother called the orphanage and told them she had found the girl in her courtyard.

The following year Li Feng had another child, this time a boy. They then contacted the family member who was raising their second girl and retrieved their daughter, now 6, bringing her home to live with them.

Their third daughter was adopted by an American family.

“Hai Yue”

Hai Yue (not her real name) was dressed in a burgundy leather jacket with faux-fur lining, covering a light turtle-neck sweater. She had long black hair which was pulled back by a silver broach. Thirty-three and married for 9 years, she also had her first child soon after getting married. This child was a girl. Six years later, she was again pregnant and had another girl. A family friend suggested that she could contact a friend of hers in another village on Hai Yue’s behalf; this friend fostered children for the orphanage. As soon as Hai Yue was brought to the recovery area of the hospital, the fosterer was called and asked to come pick up the child and bring her to the orphanage.

A year later Hai Yue gave birth to a boy.

Her second daughter was adopted into an American family in 2003.

Both women reported that they had registered their pending pregnancies with the village Family Planning Office. Registration is required by law and entitles the family an ID card for their new child. This ID card allows the mother access to prenatal care and will also allow the family to register the child for school when they get older. A person without an ID card is persona non-grata in Chinese society.

I asked them what they had done when their newborn child was a girl and they had decided they wouldn’t keep her. They said that they had returned to the Family Planning Office and reported that their newborn daughter had died. No one questioned their stories and the pregnancy was voided from the records, making them eligible to have another child.

China’s “One-Child” policy allows many rural families to have a second child if their first child is a girl. Since both Li Feng and Hai Yue had given birth to girls as first children, they were allowed another child in order to try and have a boy. Thus, both participated in what Kay Johnson terms China’s “one son or two children” exemption (“Wanting a Daughter, Needing a Son: Abandonment, Adoption, and Orphanage Care in China [Yeong & Yeong Book Company, St. Paul, MN], p. 55).

The actions of these two women has broad implications to the demographic imbalance in China. Consensus views estimate that based on census records and mortality figures obtained from Family Planning, China will experience a demographic imbalance of 40 million men in the coming decades. Since both women reported that their abandoned daughters had died, their deaths were registered in the Family Planning records and permission was given for each to have another child. However, both girls were actually alive and well in an orphanage. Thus, the mortality statistics for girls in each of their villages were inaccurate, being inflated by a false death. If their actions are similar to the thousands of other women who are abandoning their girls each year, it is probable that the mortality figures published by the Chinese Government are largely inaccurate, and the population “bubble” is exaggerated.

Next, I asked both women to elaborate on the causes for their abandoning one of their daughters. There is much speculation about this among adoptive parents. Although the answers provided by these two women are not statistically random, I feel they are representative.

I asked each birth mother to quantify on a scale of 1 to 10 how significant each of four pressures was on them to abandon.. The first was a perceived need by the birth couple to have a son to work on their farm. Both answered that this was not a significant pressure, since they perceived both sexes as being capable of farm work. Each also valued lowly the pressure felt by the birth couple to have a son to carry on the family name, although Li Feng admitted that her husband felt some desire for a son for that reason. When asked if retirement care was a major consideration, both stated that factored very low in their considerations.

Finally, I asked what role paternal grandparents played in their decision, and both indicated that this was the primary reason the birth parents had abandoned their daughter. Li Feng indicated that the paternal grandmother was especially concerned that they have a son, primarily to carry on the family name but also due to fears that the family would not be viewed well if they had two girls. Apparently having a son is viewed by some rural families as a sign of biological success, and failure to have a son is viewed as a source of shame.

When asked if the paternal grandparents had been dead at the time their daughter was born, would they have abandoned that daughter, both adamantly stated that they would have kept the girl.

These answers confirm what I have perceived from many different cultural sources in China, be they Family Planning propaganda in the countryside or answers from orphanage directors and common “man-on-the-street” interviews (see my blog “Why Girls Are Abandoned in China”, 10/26/05, http://research-china.blogspot.com). All suggest that the pressure to abandon, at least at this juncture in China’s history, comes primarily from the paternal grandparents of the child. The need for a son to work the farm or provide retirement income in old age appear to be distant secondary influences on a couple faced with keeping a second daughter. Primary is the perceived need to carry on the family name by the husband’s parents.

As we wrapped up our discussion, I posed one last question to Li Feng and Hai Yu. How often does each of them think about their “lost daughter”? The answer from both was immediate and identical: every day. Both showed in their faces the regret and shame they felt for what they had been forced to do – perhaps not forced in any literal sense, but in a cultural one. Out of respect for their elders, both of these women and their husbands felt they could not fight the pressure of their parents. Although they regretted their decisions, both admitted that if the circumstances were the same today, they would probably do it all over again.

24 comments:

Brian, love your blogs! Just curious what you used the DNA kits for?

Also, were you able to show pictures of the daughters to their birth mothers, and if so, what was their reaction?

DO any of the birth maothers WANT to be in contact with the adoptive families?

Brian,

What an amazing opportunity to speak with these two birth mothers. Getting a glimpse of their world is both sad and intriging. How painfully sad that not a day goes by that they don't think of the daughter they abandon. How tragic that if faced with the identical circumstances they would need to do the same thing. How do you change a cultural mindset after thousands of years?

I also would like to know if the birth mothers wished they had contact with the children they gave up. And, upon hearing this news of finding the birth parents, did the children (specially the 9 year old), wish to have any contact with them?

Brian

Thank you for your blogs. As a mum to 2 amazing girls born in China you give me valuable insight - this last blog will probably be very valuable when my girls grow older.

Thank you, thank you, thank you. As the mother to 2 wonderful girls from China, I knew in my heart that their birth mothers missed them and thought of them often. I never, ever believed the people who said, "You can't know that for certain." But I do know it, because my kids are so wonderful...they had to come from wonderful, generous and kind birth families...regardless of why they felt they had to leave their daughters. With this post, my intuition is confirmed.

I, too, would like to know the women's reaction to seeing their daughter's pictures and if they would like contact.

Brian,

Thanks for blogging this most valuable stuff! Tale of Two Birthmothers is the first of your blog entries I've had a chance to read. It's a must for me now to go back and read the blog from the beginning.

Thank you for this story, this is one to print out and save, so I can use it for my future child to tell about his or her birthparents.

Recently I've talked with and listened to some Dutch mothers who had to give up their child, back in the 60's. All of them thought of their children every day and carried their experience as a daily burden, as a pain in their hearts. For many, many years. Now you confirmed that the same feelings are present with Chinese birthmothers. I needed that confirmation. It will always be a guess though, since every person has his own unique story, but still, it gives me some comfort knowing that feelings like these are quite common among birthmothers all over the world...

Thanks for your research, you are doing a very valuable thing!!

By the way, reading this article, I have the idea, that in future generations, the pressure of the grandparents will become a lesser issue, I wonder what kind of effect this will have for the coming years...

This gives me such a different perspective on my daughter's birth parents' reasons for abandoning her. I can't even really wrap my head around it yet.

This makes so much sense to me! Think about all the Chinese movies and literature out there--there's always the powerful influence of the husband's parents.

I wonder how the birth mothers feel about their daughters living their lives in foreign lands.

I'll just throw out my other questions, and if you have time, please share your thoughts: Do you think they hope that their daughters are adopted in-country rather than by Westerners? Is it common knowledge that only a few orphanages adopt out of country? Or is the impression that any baby sent to any orphanage has a chance to be adopted by eager foreigners?

Are they at all ashamed of themselves for abiding by their in-law's wishes, or is it such a given that while there is regret there is no shame?

What is their impression of Western families--do they think we're all tall, rich, and fat? And do they hate or resent us? That's the question that's always in the back of my mind.

I also wonder why so many of us adoptive parents never hear this part of the Chinese adoption story from our agencies. I had the impression that these were the main reasons so many girls are abandoned: restrictive government policies, extreme poverty, and the "social security" issue--the last of which is somewhat romantically explained as simply being part of 3000 years of culture/philosophy. I remember hearing only a passing reference to pressure from the inlaws. This pressure is just as much a part of Chinese culture as anything else we all try to understand and accept.

Perhaps the Chinese government doesn't want the true weight of this pressure exposed, because the implication is that powerless mothers and fathers are in fact forced to abandon female children that the parents would otherwise choose to raise--forced not by dire economic circumstances, or the necessity of social security, but literally forced by other people.

This is making my eyes sting.

Brian, your post supports two convictions I already held in my heart: my daughter's birth mother loved and wanted her, and, in general, in-laws are just awful.

This hurts my heart to read. My wife and I adopted from Yifeng (near Nanchang) in July, definately a rural area. Reading this makes it all the more important to me to honor the birthparents of this child in our care. I grieve for their loss as much as I celebrate our good fortune in receiving into our lives this wonderful girl who is pure magic.

Brian,

Thank you so much for your blogs and the incredible insight they give us and our children. Although we'll most likely never know the truth about our daughter's birthparents reason for not keeping her now we have another aspect to explore. Up until reading your blog this idea of pressure from paternal parents was not shared as much as the thoughts that parents left their daughter's for economic reasons or traditional values. I already knew in my heart that my daughter's birthmother must think of her often. As a birthmother myself I can not imagine the grief of having abandoned my child no matter what the circumstances. I also can not imagine what it does to the relationship between the birthparents and paternal grandparents.

I too wonder what the birthparents would do if they could see a photo of or even meet their birth daughters that have been adopted. Did they ask about them?

Brian, Thank you so much for this! I am printing it out for my daughter when she gets older. I too knew in my heart that the birthmother of my Amazing Amelia must think of her daily.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart for doing the work you do. It's all part of the bigger picture of our lives.

I appreciate the information you are publishing here, as it gives a differing perspective to that which we are normally exposed.

Both the entry about 'Two Birth Mothers' and the earlier Hunan trafficking issue have raised strange emotions - my daughter was brought home from the Hunan Province this past May. I do not now have the words necessary to convey the many thoughts swirling about inside my head.

(Enlightened and disturbed.)

Thanks for posting this. I found your conclusions challenging. For some time, my (admittedly impressionistic) hunch has been that a growing number of China's orphans are being abandoned largely because of the breakdown in rural extended family networks, due to the dislocations caused by China's pell-mell urbanization and industrialization. The cases you cite argue the opposite: that, in the countryside at least, family traditions remain sufficiently intact so as to have led these parents to give up their daughters.

That said, it seems to me we shouldn't expect, or want, a single explanation for so complex and multi-faceted a social problem as this, with its urban as well as rural, economic as well as cultural, dimensions. In any event, thanks much for this stimulating piece.

If you get a chance, if you know, please let us know the birthmother's response to their daughters living overseas and if they would want contact.

Mimi

Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!

I have a daughter from Jiangxi who just have turned one year. At her birthday I felt very sad when I thought about what her birth parents probably felt this day.

Right now I think a lot of her birth parents and their thoughts and feelings. The pain and grief of (probably) never be able to know what happened then to their sweet little girl.

Thank you for this little piece of a very large puzzle! I, like all the others did not think about grandparents being the ones behind the pressure to abandoning their children! I would love to hear your answers to all the questions here also.

Autumndays

Brian,

Your articles are so well written...keep asking those questions, as the answers may help us explain to our children their early history.

Our children were not born in China, but they were born in another Asian country and in each case, it is evident from the "records" that we have that the grandparents had a significant role in the placement of the child with the orphanage. In one file, it is clear that both sets of grandparents were involved in the decision.

Dear Brian,

Thank you for your great work and your wonderful blogs. I thought you would find the following interesting.

In a recent UK Times article entitled Chinese Facing Jail to Protect Unborn Girls (published 12/27/05), the following quote was presented. "Li Li, a doctor from the First People’s Hospital of Datong in the northern Shanxi province, told The Times: “It’s usually the grandparents who want to know the sex. The younger generation don’t care so much."

The article can be found at http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,25689-1959596,00.html.

Keep up the excellent work.

Lisa

San Diego

is the internet being used by chinese birthmothers and adoptive parents to try to match up their children? it seems like this would be the next logical progression, especially with the availability of DNA testing. will we see the day when our kids can find their birth parents in china?

Dear Brian and Lan.......you two are the best!! You have given to us the greatest gift that we could have imagined for our daughter. One day, if she would like to know, we can share with her the identity of her birth parents and their family. We have validated that our daughter is connected to the mother (Hai Yue)in your story via the positive (99.9998) results of the DNA testing. We have also been in contact with the birth family and they are absolutely thrilled to know that their daughther is with such a big family (three older brothers) and is well cared for. We will continue to communicate with the birth parents as much as they desire. We can not thank you enough for your invaluable assistance. See you in March at Lucy's.

As we try to understand the motives of Chinese birth mothers who abandoned baby girls in response to pressure from in-laws, we might want to keep in mind that we had an analogous phenomenon in the U.S. not long ago. Although the specifics are different, you might want to think about the many American girls who were forced *by their own parents* to give up their babies. (See Ann Fessler's recent book, "The Girls Who Went Away : The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade"). Fessler talks about pregnant girls who were literally sent away, to be hidden from family, friends, and neighbors until they gave birth and their babies were given over for adoption. In the American case, this pressure was driven by the stigma of unwed motherhood. For young people today, that stigma is probably as incomprehensible as Chinese boy preference is to the readers of this blog. But U.S. society changed, and Chinese society is changing too.

Post a Comment