The heat was stifling even on that mid-May morning. My wife and young daughter Meilan, with my wife's sister in tow, had made the short bus trip from Guangzhou to Foshan. Our destination was Foshan's "Zumiao Temple", the temple of the ancestors.

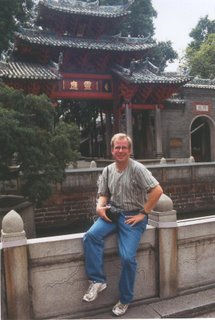

The heat was stifling even on that mid-May morning. My wife and young daughter Meilan, with my wife's sister in tow, had made the short bus trip from Guangzhou to Foshan. Our destination was Foshan's "Zumiao Temple", the temple of the ancestors.I had been there twice before, the first time on my first return trip to Guangdong after adopting Meikina in 2000. Whenever I return to Guangdong, I feel the need to come to this large and beautiful temple, in order to offer up a small prayer to the ancestors of my three daughters.

It isn't a prayer to them really, but more of a token offering of thought. I feel it my obligation to occasionally bring myself to stop and thank them for the three beautiful Chinese spirits that have been placed in my care, three children who are the culmination of the lives of all those that preceded them. I come to this temple to give quiet thanks, and to ponder how I can best bring an appreciation to my kids of the tremendous country from which they sprang.

My family feels I have an irrational affection for China. Like an imperfect spouse, I speak proudly of the things I love about China, and quietly ignore her failings. It is not that I am not aware of them, but I simply seek to convey to my children at every turn that they can be proud of their heritage, that China is a wonderful country, and that those who came before them accomplished things that few other nations ever could.

In the six years that I have been researching in China, I have come to notice and appreciate the sometimes vast cultural differences between China and my own homeland, the United States. In studying and gaining insight into China's people and history, I have gained an ever-increasing respect for China's greatness, but also an increased appreciation for the land in which I live.

One of the most noticeable differences between China and the United States involves the attitudes of each government towards its citizens. As I have researched and traveled throughout much of China, I frequently sense an almost palpable fear on the part of the Chinese for their government. This is most apparent when dealing with the police. Whereas in the United States we are taught from our youngest days to trust the police, in China it is often just the opposite. Few in China trust the police. Often, the police abuse their positions of power to take unfair advantage of the citizens.

One recent case, published widely in Chinese newspapers, serves to illustrate. She Xiang Lin was a policeman in Hubei province. In January 1994, his wife disappeared, and her family suspected she had been murdered by her husband. They exerted tremendous pressure on the police to arrest the husband for murder, and when a badly decomposed body was found in April, the husband was arrested. After a series of beatings, he confessed to killing his wife. He was sentenced to death, a sentence that was later commuted to 15 years in prison.

In April, his wife returned to the village with her new husband, apparently not dead after all. Everyone involved urged the immediate release of her former husband, who had by this time served over eleven years in a brutal prison. The police, who had apparently coerced a confession from the husband through repeated beatings, are now trying to decide whose body was found in the first place.

These type of stories are myriad. For the most part, members of government are seen as self-serving, corrupt people. The officials do little to dispel this notion, as a trip into any village or town will attest. In the little town of Maogang (south of Maoming, Guangdong Province) for example, the city government offices are housed in a building that is on the scale of the Mirage resort in Las Vegas – huge, palatial and completely unnecessary, except to increase their perceived stature in the community and among the citizens. All around farmers scrap to make an existence, but the government officials drive their nice cars and work in their windowed offices in the palace on the hill.

The United States, for all its political weaknesses, has at least this of which it can boast – its government is ultimately responsible to the people. Its system of checks and balances, combined with the Constitutionally protected free press, create an attitude of accountability to the citizens which China's government lacks. The Chinese are dumbstruck when they see high governmental officials in the U.S. being brought down by the press, for if a newspaper published reports of corruption in China it would be destroyed. In one country you have trust and confidence, in the other distrust and fear.

This is manifested by the high degree of fear and distrust that I encounter while researching. Although many directors are intellectually committed to helping the children they have cared for, they are nevertheless fearsome of reprisals from those above them. Additionally, they are afraid that those in their own ranks will report them to their superiors. The entire governmental structure in China is held together by a glue of fear and insecurity.

But the absence of a free press in China means that graft and corruption usually goes unexposed and unpunished. Applicants for many government jobs willingly pay huge sums in "application fees" knowing that the access gained by their new positions will bring great returns on their investment. Growing dissatisfaction among China's rural communities is kept hidden. The rebellion in December by farmers in Guangdong Province in which 20 village citizens were seriously injured by police went totally unreported in the Chinese press. The Chinese government reports that 87,000 such "disturbances" occurred in 2005 alone.

Things are changing, however. China seems tentatively committed to eradicating the enormous graft and corruption problem that has plagued its system for generations. The fact that the wrongly-convicted man's story made headlines throughout China shows that greater leeway is being given the press. The internet, no matter how hard the government attempts to limit its access, is granting the Chinese an unprecedented look into the outside world. A few months ago I spied a youth wearing a t-shirt with the words, "Liberty and Justice for all".

The question is whether the change is coming fast enough. Whenever I discuss with the Chinese the benefits of their government, they grow angry and shout how much they hate their government. It seems that especially in the countryside the people are like a pot of water heated to 211 degrees. The question is whether change will come before a small spark pushes the pot to boiling.

As I sat in the temple contemplating the many aspects of Chinese history and culture, my mind gave thanks to the contributions China has made to the world. My mind reflects on the China in the early fifteenth century, when its civilization was expanding, and its technological abilities were unsurpassed. Then a visionary emperor sent forth his huge naval ships to explore and open trade routes to the entire world. The seven voyages of Zheng He showcased China's capabilities, and placed China in the position to become the world's super-power.

But a storm and fire in Beijing changed all that. The emperor's expansionist policies were viewed as having offended the gods, and he died in exile. The next emperor destroyed the records of Zheng He's journeys (which some believe brought the Chinese to America 70 years before Columbus), and turned China inward. It would remain so for five hundred years. As I stand in front of the golden Buddha, my heart breaks at the loss of potential that China suffered by the actions of that one man.

I love China. I love all that is good, all that is great about her. I love her rich culture, and immense history. I love her emphasis on family, with families living in close proximity together for generations. I love watching grandparents play with their small grand kids, and communities gathering together for festivals. I love the thousands of men and women who lived and died to bring my daughters to life, and into my family. Thus, I return annually to pay them respect in an ancient temple in Foshan.

3 comments:

My daughter (adopted from China) and I (white) live in a mostly-black neighborhood in Brooklyn, NY. We live on a great block and my daughter has many friends here. When she was 5 or 6, one day she came in from playing outside and told me that, contrary to what she had been taught at school and by me, her friends had been taught by their parents that the policeman was not necessarily their friend. And this has been echoed by black police officers who live in our condo, one of whom is a lawyer for NYPD and spends her days straightening out the messes caused by her fellow officers.

I am not saying that this rises to the level of abuse by police in China but it's something those of us living in the U.S.A. who are not people of color (especially some colors in particular) may overlook.

Amen!

Jenna

It should come as virtually no surprise that Chinese citizens are fearful not only of the police, but of government officialdom. Anyone who knows anything about recent Chinese history (from 1949 onward) should be accutely aware of the pervasive system of control by fear perpetrated within the Chinese borders.

Anyone wishing a crash course in China's recent history might well consider reading the recently released, and easy to read (albeit lengthy) book , "Mao - The Unknown Story", co-written by the author of Wild Swans, Jung Chang, and her husband Jon Halliday.

Post a Comment