A recent article attributed to Lauren Bossen summarizing various studies on China’s sex imbalance raises some interesting questions as to the motives of birth parents in abandoning their daughters. The following essay recaps my experiences in determining these motives, and conflicts with some of those made in Bossen’s article.

(http://www.zmag.org/content/showarticle.cfm?SectionID=103&ItemID=8891).

_______________________________

As adoptive parents, we often wonder what motivated the birth parents of our children to abandon them. In the course of my research, I have asked the opinion of scores of couples, orphanage directors, taxi drivers, and anyone else that I think might have an idea of why they feel it is happening. One common answer emerges, although the problem is admittedly complex.

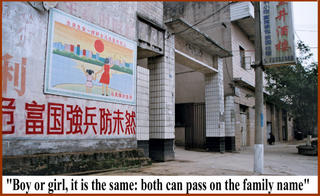

In addition to providing family planning counseling, the local Family Planning offices are responsible for promulgating the “one-child” policy to the citizens of their jurisdiction. Public billboards promoting the policy are ubiquitous in China’s countryside. Although the billboards, wall murals, and hillside slogans generally promote the one-child policy, frequently they also address the issue of female abandonment. A survey of these specific messages provides one with an idea of what the local officials feel are the main reasons for child abandonment. Combining the themes of the family planning propaganda with the anecdotal evidence collected from average citizens, a clear hierarchy of reasons for abandonment emerges.

It is important to keep a few things in mind when drawing assumptions regarding this topic. First, the economic situation is changing rapidly in China. Twenty years ago, economic pressures relating to having a second child (medical attention, schooling expenses, governmental fines imposed for second children) were much different than today. Most families have seen their incomes increase dramatically in the last 10 years, even in the rural countryside. Increased economic opportunities have dramatically altered the intrinsic worth of girls in China also.

Second, societal attitudes are also changing. As China embraces Western culture, what I term "Chinese traditionalism" is on a decrease. Especially among the youth and young adults, strict observance of Chinese tradition is waning. Cultural biases are also changing, and this has dramatic implications when it comes to attitudes about girls.

Thus, we must be careful when looking at statistics and anecdotal evidence from the 80s and 90s. My observations are limited to conditions and attitudes today, and might not be applicable to conditions and motivations prominent ten or more years ago.

The Family Planning propaganda regarding abandonment is almost universal in it’s message: “Boy or girl, it is the same -- Both can carry on the family name.” This message is by far the most prominent when one studies the “official” message from the Chinese government.

It is important to realize that in China a woman doesn’t change her name when she marries. The issue of passing on the family names relates to the children that the married couple will have. In almost all situations, the children of a married couple will be known by, and will carry, the family name of the father.

In discussing this topic with young marrieds, I have yet to find a young husband or wife that feels the family name is important enough to abandon their daughter. When I ask if their parents feel similarly, I often discover that the attitudes of the older generation are not the same. In fact, especially among the paternal grandparents, the desire to have a male child to continue the family name is most strong. Interviews with many couples convince me that the primary pressure to abandon originates with the parents of the father.

This conclusion is re-enforced by the Family Planning propaganda, as well as anecdotal evidence from international adoptions. The example of the family planning mural I saw in Lianjiang, Guangdong Province (see above) clearly illustrates the problem of grand-parent attitudes towards female children. Thus, it is probable that the Family Planning messages are aimed primarily at the grand-parents in China, not the parents themselves. In my discussions with many young parents, I see very little preference for boy children.

When analyzing the finding ads from the various orphanages in China, a trend emerges: fewer and fewer girls are being found. This trend is almost universal across China, with a few exceptions.

It is of course dangerous to stereotype the multitude of reasons why a family might decide it in the best interest to abandon their daughter. As with any situation, each family is unique in their economic, cultural and familial standing. But broad generalizations can nevertheless be made. Minority factors include a complete lack of medical insurance among China's poorest families, resulting in wanted children being abandoned due to perceived or actual medical conditions. Lack of financial resources to educate register (government imposed fees) and educate a child certainly play an important role. Bossen speculates that China's rural land policies play an important role in female abandonment. This governmental policy gives rural families an additional acre of farm land in their village when a child is born. If that child is a boy, stewardship of the land falls to the male child when they marry; it reverts back to the government when the female child marries. The purpose of this policy is to encourage inter-generational stability in the rural villages, and to discourage the migration of families into the urban areas. I have found no families or individuals, however, that have even considered China's land policy in conjunction with family size or make-up.

One point Bossen makes, and with which I agree with, is the misperception we have that the rural farmers in China need a son to farm the land. This is simply not the case. Women today work the farms alongside their husbands or fathers. In addition, China's growing industrial manufacturing base has brought substantial opportunity to women in the countryside. The economic value of male and female children has shrunk considerably in the last 20 years.

In summary: My experiences in researching in China has led me to the conclusion that the primary force behind the problem of female abandonment is pressure brought to bear on the parents by the grandparents, usually from the father's side. Although other factors certainly play a role, they are secondary to "China traditionalism", the belief among older Chinese in the importance of passing on the family line through male children. As the traditionalist grandparent population continues to decline, pressure to abandon will also decline, resulting in fewer and fewer found girls.